13.3.00

C. Wright Mills, Free Radical

by Todd Gitlin*

Whether or not the rest of this sentence sounds like an oxymoron, C. Wright Mills was the most inspiring sociologist of the second half of the twentieth century, his achievement all the more remarkable for the fact that he died at 45 and produced his major work in a span of little more than a decade. For the political generation trying to find bearings in the early Sixties, Mills was a guiding knight of radicalism. Yet he was a bundle of paradoxes, and this was part of his appeal whether his readers were consciously attuned to the paradoxes or not. He was a radical disabused of radical traditions, a sociologist disgruntled with the course of sociology, an intellectual frequently skeptical of intellectuals, a defender of popular action as well as a craftsman, a despairing optimist, a vigorous pessimist, and all in all, one of the few contemporaries whose intelligence, verve, passion, scope—and contradictions—seemed alive to most of the main moral and political traps of his time. A philosophically-trained and best-selling sociologist who decided to write pamphlets, a populist who scrambled to find what was salvageable within the Marxist tradition, a loner committed to politics, a man of substance acutely cognizant of style, he was not only a guide but an exemplar, prefiguring in his paradoxes some of the tensions of a student movement that was reared on privilege, amid exhausted (1) ideologies, yet hell-bent on finding, or forging, the leverage with which to transform America root and branch.

In his two final years, Mills the writer became a public figure, his tracts against the Cold War and U. S. Latin American policy more widely read than any other radical's, his Listen, Yankee, featured on the cover of Harper's Magazine, his "Letter to the New Left" published in both the British New Left Review and the American Studies on the Left and distributed, in mimeographed form, by Students for a Democratic Society. In December 1960, cramming for a television network debate on Latin America policy with an established foreign policy analyst (2), Mills suffered a heart attack, and when he died fifteen months later he was instantly seen as a martyr. SDS's Port Huron Statement carries echoes of Mills' prose, and Tom Hayden, its principal author, wrote his M. A. thesis on Mills, whom he labeled "Radical Nomad," a heroic if quixotic figure who, like the New Left itself, muscularly tried to force a way through the ideological logjam. After his death, at least one son of founding New Left parents was named for Mills, along with at least one cat, my own, so called, with deep affection, because he was almost red.

Mills' writing was charged—seared—by a keen awareness of human energy and disappointment, a passionate feeling for the human adventure and a commitment to dignity. In many ways the style was the man. In a vigorous, instantly recognizable prose, he hammered home again and again the notion that people lived lives that were not only bounded by social circumstance but deeply shaped by social forces not of their own making, and that this irreducible fact had two consequences: it lent most human life a tragic aspect with a social root, and also created the potential—if only people saw a way forward—of improving life in a big way by concerted action.

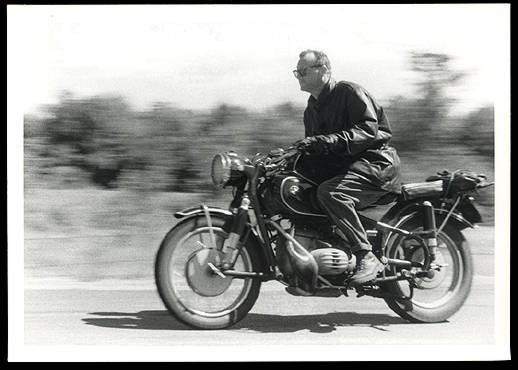

Mills insisted that a sociologist's proper subject was the intersection of biography and history. Mills invited, in other words, a personal approach to thought as well as a thoughtful approach to persons, so it was no fault of his own that he came to be admired (and sometimes scorned) as a persona and not only a thinker, and that long after his death he still demands to be taken biographically as well as historically. In SDS, we did not know Mills personally, for the most part, but (or therefore) a certain mystique flourished. It was said (accurately) that Mills was partial to motorcycles, and that he lived in a house in the country that he had built himself. It was said (accurately) that he had been divorced more than once, and (inaccurately) that he had been held back from a full professorship at Columbia because of his politics. If his personal life was unsettled, bohemian, and mainly his own in a manner equivalent to his intellectual journey and even his style, the fit seemed perfect.

Mills himself was not a man of political action apart from his writing, yet it was as a writer that he mattered, so his inclination to go it alone was far from a detriment. "I have been intellectually, politically, morally alone," he would write. "I have never known what others call 'fraternity' with any group, however small, neither academic nor political. With a few individuals, yes, I have known it, but with groups however small, no....And the plain truth, so far as I know, is that I do not cry for it." (3) His forceful prose, his instinct for significant controversy, his Texas hell-for-leather aura, his reputation for intellectual fearlessness and his passion for craftmanship (one of his favorite words) seemed all of a piece. A free intellectual tempted by action, he served as an engagé father or uncle figure, an outsider who counterposed himself not only to liberal academics who devoted themselves to explaining why radical change was either foreclosed or undesirable, but also to the court intellectuals, the fawning men of power and quantification who clustered around the Kennedy administration and later helped anoint it Camelot. The Camelot insiders might speak of a New Frontier while living in glamour and reveling in power, while Mills, the loner, the anti-bureaucrat, was staking out a New Frontier of his own.

Mills' output was huge in a short life, and here I can pick up only a few themes. He produced his strongest work in the Fifties—White Collar (1951), The Power Elite (1956), The Sociological Imagination (1959)—banging up against political closure and cultural stupefaction. These books were, all in all, his major statements on what he liked to call "the big questions" about society, preceding the pamphlets, The Causes of World War Three (1958) and Listen, Yankee: The Revolution in Cuba (1960), along with an annotated collection, The Marxists (1962). (He also left a plethora of unfinished, ambitious projects, not only polemical but deeply empirical.) Next spring, a collection, C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings, edited by Kathryn Mills with Pamela Mills, is be published by the University of California Press. This volume serves as a superb accompaniment to Mills' published books precisely because—as with Albert Camus, James Agee, and other exemplars of radical individualism—the personal and the political embraced each other so closely.

One thing that stands out in the letters is just how deeply, fearlessly American Mills was. Growing up in Texas, schooled in Austin and Madison, living in Maryland and New York, Mills was full of frontier insouciance: "All this national boundary stuff is a kind of highway robbery, isn't it?" (4) "Intellectually and culturally I am as 'self-made' as it is possible to be," he wrote. (5) His "direction," he wrote, was that "of the independent craftsman." (6) "I am a Wobbly, personally, down deep and for good....I take Wobbly to mean one thing: the opposite of bureaucrat." (7) In the midst of his activist pamphleteering, he still wrote: "I am a politician without a party" (8) —or to put it another way, a party of one. So it only reinforced Mills' reputation that he proved to be a martyr of a sort—not a casualty of jousts with political enemies but, in a certain sense, a casualty of his chosen way of life. This physically big ("Take it big!" he liked to say), prepossessing, hard-driving man was more frail than he would want to let on, or know. That he suffered a grave heart attack while feverishly preparing for his TV debate on Latin American policy felt like a scene from High Noon, except that Gary Cooper is supposed to win the gunfight.

His prose was hard-driving, not frail, and this was not incidental to his appeal. His writing was instantly recognizable, frequently emulated (look at the early passages of the Port Huron Statement and other SDS publications of the time), and properly labeled muscular. It was frequently vivid and moving, often pointedly colloquial, though at times clumsy from an excess of deliberation (Mills worked hard for two decades to perfect his style). He was partial to collisions between nouns of action and nouns of failure—"showdown" and "thrust" versus "drift" and "default." He was partial to polemical categories like "crackpot realism" and "the military metaphysic." This style was, in the best sense of the word, masculine, though hardly macho—a macho writer would not be haunted by the prospect of mass violence, or write that the "central goal of Western humanism [was]...the audacious control by reason of man's fate." (9)

Mills' willingness to go it alone ran deep. In a letter to the student newspaper at Texas A & M, written in his freshman year, in the thick of the Great Depression, the nineteen-year-old Mills was asking: "Just who are the men with guts? They are the men...who have the imagination and the intelligence to formulate their own codes; the men who have the courage and the stamina to live their own lives in spite of social pressure and isolation." (10) Rugged stuff, both democratic and noble, Whitmanian and Hemingwayesque, in a manner that has come to be mocked more than read. A quarter of a century later, the stance implied by the teenage Mills would have been called existentialism, and when transposed into a more urgent prose translated from the French, would have become—was—the credo of teenage boys with the audacity to think they might change the world. Later, this style would be burlesqued as macho, brutal, distinctly (and pejoratively) "male." But the accusation of male exclusivity would miss something central to Mills' style, namely the tenderness and longing that accompanied the urge to activity—qualities which carried a political hopefulness that was already unfashionable when Mills used it and has now virtually vanished. (11) To be precise, the spirit of these words was in the best sense adolescent.

I speak of adolescence here deliberately and without prejudice. The adult Mills himself commended the intensity and loyalty of adolescence: "I hope that I have not grown up. The whole notion of growing up is pernicious, and I am against it. To grow up means merely to lose the intellectual curiosity so many children and so few adults seem to have; to lose the strong attachments and rejections for other people so many adolescents and so few adults seem to have....W. H. Auden recently put it very well: 'To grow up does not mean to outgrow either childhood or adolescence but to make use of them in an adult way.'" (12) Mills could never be dismissive about ideals or, in the dominant spirit of his time, consider idealism a psychiatric diagnosis.

"I have never had occasion to take very seriously much of American sociology as such," Mills had the audacity to write in an application for a Guggenheim grant in 1944. (13) He told the foundation that he wrote for journals of opinion and "little magazines" because they took on the right topics "and even more because I wished to rid myself of a crippling academic prose and to develop an intelligible way of communicating modern social science to non-specialized publics." At twenty-eight, the loner already wished to explain himself; the freelance politico wished to have on his side a reasoning public without letting it exact a suffocating conformity as the price of its support. Mills knew the difference between popularity, which he welcomed as a way to promote his ideas, and the desire to live a free life, which was irreducible; for (he wrote in a letter at forty) "way down deep and systematically I'm a goddamned anarchist." (14)

Not any old goddamned anarchist, however. Certainly not an intellectual slob. He respected rigor, aspired to the high calling of craft, was usually unafraid of serious criticism and liked to respond to it, liked the rough and tumble of straightforward dispute. Craft, not methodology—the distinction was crucial. Methodology was rigor mortis, dead rigor, rigor fossilized into arcanery of statistical practice so fetishized as to have eclipsed the real stakes of research. Craft was work done with respect for materials, clarity about objective, and a sense of the high drama and stakes of intellectual life. The Sociological Imagination (1959), his most enduring book, ends with an appendix, "On Intellectual Craftmanship," that in turn ends with these words (which, as it happens, in college, I typed on an index card and posted next to my typewriter, hoping to live up to the spirit):

Before you are through with any piece of work, no matter how indirectly on occasion, orient it to the central and continuing task of understanding the structure and the drift, the shaping and the meanings, of your own period, the terrible and magnificent world of human society in the second half of the twentieth century. (15)

Some mission for pale sociology! His major books were driven by large topics, not method or theory, yet they were also driven by a spirit of adventure. (He was so far from main thrust as to prefer the term "social studies" to "social sciences.") (16) That a sociologist should work painstakingly, over the course of a career, to fill in a whole social picture should not seem as remarkable as it does today. In The Sociological Imagination, Mills grandly excoriated the two dominant tendencies of mainstream sociology, the bloated puffery of Grand Theory and the microscopic marginality of Abstracted Empiricism, in terms that remain as important and vivid (and sometimes hilarious) today as they did forty years ago. All the more so, perhaps, because sociology has slipped still deeper into the troughs Mills described. He would be amused at the way in which postmodernists, Marxists, and feminists have joined the former grandees of theory on their "useless heights," (17) claiming high seriousness as well as usefulness for their pirouettes and performances, their monastic and masturbatory exercises, their populist cheerleading, political wishfulness, and self-important grandiosity. He would not have thought Theory a serious blow against irresponsible power. I think he would have recognized the pretensions of Theory as a class-bound ideology—that of a "new class," if you will—to be criticized just as he had exposed the supervisory ideology of the abstracted empiricists in their research teams doing the intellectual busywork of corporate and government bureaucracies. I think he would also have recognized, in the grand intellectual claims and political bravado of Theory, a sort of Leninist assumption—a dangerous one—about the irreplaceably high mission of academics.(18)

Of course Mills had a high sense of mission himself—not only his own mission, but that of intellectuals in general and social scientists in particular. He was committed to intellectual work guided by truth to what Max Weber had called a "calling," a vocation in the original sense of being summoned by a voice. Not that Mills (who with Hans Gerth edited the first significant compilation of Weber's essays in English) agreed with Weber's conclusion that "science as a vocation" and "politics as a vocation," to name his two great essays on the subject, needed to be ruthlessly severed. Not at all. Mills thought the questions ought to come from values, but the answers should not be rigged. A crucial difference! If the results of research made you grumpy, too bad. But he also thought that good social science became good politics when it moved into the open and generated public discussion. He came to this activist idea of intellectual life partly by temperament—he was not one to take matters lying down—but also by deduction and by elimination. For if intellectuals were not going to break the intellectual logjam, who would?

This was not, for Mills, a merely rhetorical question. It was a question that, in the Deweyan pragmatic spirit that had been the subject of his doctoral dissertation, required an experimental answer, an answer that would unfold in real life through reflection upon experience. For his conclusion after a decade of work was that if one were looking for a fusion of reason and power—at least potential power—there was nowhere else to look but to intellectuals. Mills had sorted through the available history-makers in his books of the late 1940s and 1950s—labor in The New Men of Power, the middle classes in White Collar, and the chiefs of top institutions themselves in The Power Elite. Labor was not up to the challenge of structural reform, white collar employees were confused and rearguard, and the power elite was irresponsible. Mills concluded (partly by elimination) that intellectuals and only intellectuals had a fighting chance to deploy reason. Because they could embody reason in addressing social problems when no one else could do so, it was incumbent upon them to try, in addressing a problem, to have "a view of the strategic points of intervention—of the 'levers' by which the structure may be maintained or changed; and an assessment of those who are in a position to intervene but are not doing so." (19)

As he would write in The Marxists, a political philosophy had to encompass not only an analysis of society and a set of theories of how it works but "an ethic, an articulation of ideals." (20) It followed that intellectuals should be explicit about their values and rigorous in considering contrary positions. It also followed that research work should be supplemented by blunt writing that was meant to inform and mobilize what he called, following John Dewey, "publics." In Mills' words, "The education and the political role of social science in a democracy is to help cultivate and sustain publics and individuals that are able to develop, to live with, and to act upon adequate definitions of personal and social realities." (21)

To a degree that has come to seem controversial today, Mills was not cynical about the importance of reason—or its attainability, even as a glimmering goal that could never be reached but could be approximated ever more closely, asymptotically. To the contrary. He wrote about the Enlightenment without a sneer. (22) He thought the problem with the condition of the Enlightenment at mid-century was not that we had too much Enlightenment but that we had too little, and the tragedy was that the universal genuflection to technical rationality—in the form of scientific research, business calculation, and state planning—was the perfect disguise for this great default. The democratic self-governance of rational men and women was damaged partly by the bureaucratization of the economy and the state. (This was a restatement of Weber's great discovery: that increased rationality of institutions made for less freedom, or least no more freedom, of individuals.) And democratic prospects were damaged, too—in ways that Mills was trying to work out when he died—because the West was coping poorly with the entry of the "underdeveloped" countries onto the world stage, and because neither liberalism (which had, in the main, degenerated into techniques of "liberal practicality") nor Marxism (which had, in the main, degenerated into a blind doctrine that rationalized tyranny) could address their urgent needs. "Our major orientations—liberalism and socialism—have virtually collapsed as adequate explanations of the world and of ourselves," (23) he wrote. This was dead on.

It goes without saying that Mills felt urgently about the state of the world—a sentiment that needed no excuse during the Cold War, though one needs reminders today of just how realistic and anti-crackpot it was to sound the alarm about the sheer world-incinerating power that had been gathered into the hands of the American national security establishment and its Soviet counterpart. It cannot be overemphasized that much of Mills' work on power was specific to a historical situation that can be described succinctly: the existence of national strategies for nuclear war. Mills made the point intermittently in The Power Elite, and more bluntly in The Causes of World War Three, that the major reason America's most powerful should be considered dangerous was that they controlled weapons of mass destruction and were in a position not only to contemplate their use but to launch them. Mills' judgment on this score was as acute as it was simple: "Ours is not so much a time of big decisions as a time for big decisions that are not being made. A lot of bad little decisions are crippling the chances for the appropriate big ones." (24) Most of the demurrers missed this essential point. (25) To head off pluralist critics, Mills acknowledged that there were policy clashes of local and sectoral groups, medium-sized business, labor, professions, and others, producing "a semiorganized stalemate," but thought the noisy, visible conflicts took place mainly at "the middle level of power." (26) As for domestic questions, Mills probably exaggerated the unanimity of powerful groupings. He was extrapolating from the prosperous, post-New Deal, liberal-statist consensus that united Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy more than it divided them. Like most observers of the Fifties, he underestimated the potential for a conservative movement. (27) But about the centralization of power where it counted most, he was far more right than wrong.

One has to recall the setting. Mills died a mere seven months before the Cuban Missile Crisis came within a hair's breadth of triggering a nuclear war. Khrushchev's recklessness in sending missiles to Cuba triggered the momentous White House decisions of October 1962. Enough time has passed since them without thermonuclear war that an elementary point has to be underscored: the fact that Kennedy's inner circle backed down from the brink of war was not inevitable. It was, shall we say, contingent rather than structural. A handful of men—they were men—had full opportunity to make the wrong decision and produce mass death. They made the right decision, as did Khrushchev, in the end, and the superpowers clambered back from the precipice. At that world-shattering moment when eyeballs faced eyeballs, the men in charge had the wisdom not to blow their eyeballs and millions of other people's away. They had the opportunity and the means to make other decisions. They were hair-raisingly close. The fact that they didn't make the wrong decisions doesn't detract from Mills' good judgment in taking seriously this huge fact about America's elite: that they were heading toward a crossroads where they might well have made a momentous, irreversible wrong turn. Who these men were, how they got to their commanding positions, how there had turned out to be so much at stake in their choices—there could be no more important subject for social science. Whatever the failings of Mills' arguments in The Power Elite, his central point obtained: the power to launch a vastly murderous war existed, in concentrated form. This immense fact no paeans to pluralism could dilute.

Mills not only invoked the sociological imagination, he practiced it brilliantly. Careful critics like David Riesman, who thought Mills' picture of white collar workers too monolithically gloomy, still acknowledged the insight of his portraits and the soundness of his research. (28) Even the polemical voice of a Cuban revolutionary that Mills adopted in Listen, Yankee—a voice he thought that Americans, "shot through with hysteria," (29) were crazy to ignore—was quietly shaped by Mills' ability to grasp where, from what milieu, such a revolutionary was "coming from." While he did not fully appreciate just how much enthusiasm Americans could bring to acquiring and using consumer goods, he did prefigure one of the striking ideas of perhaps his most formidable antagonist, Daniel Bell—namely, the centrality, in corporate capitalism, of the tension between getting (via the Protestant ethic) and spending (via the hedonistic ethic). (30)

In a sense, Mills' stirring invocation to student movements at the turn of the Sixties stemmed from his sociological imagination. He was deeply attuned to the growth of higher education and the growing importance of science in the military-corporate world. More than any other sociologist of the time, Mills anticipated the ways in which conventional careers and narrow life-plans within and alongside the military-industrial complex would fail to satisfy a growing proto-elite of students trained to take their places in an establishment that they would not judge worthy of their moral vision. If he exaggerated the significance—or goodness—of intellectuals as a social force, this was also a by-product of his faith in the powers of reason. Believing that human beings learn as they live, he was on the side of improvement through reflection. Thus, he thought that Castro's tyranny, and other harsh features of the Cuban revolution, were "part of a phase, and that I and other North Americans should help the Cubans pass through it." (31) In his last months, he was increasingly disturbed about Fidel Castro's trajectory toward Soviet-style "socialism," and restive in the vanishing middle ground. There are two fates that afflicted free-minded radicals in the twentieth century: to be universally contrarian and end up on the sidelines, or to hope against hope that the next revolution would invent a new wheel. On the strength of Mills' letters, my guess is that Mills would have gone through the second fate to the first, yet without reconciling himself to the sidelines.

Of course, no one can know where Mills might have gone as the student movement radicalized, grew more militant, more culturally estranged, frequently reckless and self-destructive, partly from desperation, partly from arrogant self-inflation. Of the generation of intellectuals who thrived in the Fifties, Mills more than any other was in a position to grasp not only the strength of what was happening among students, blacks, and women, but also the wrongheadedness and tragedy; might have spoken of it, argued for the best and against the worst, in a voice that would have been hard to ignore—though it would probably have been ignored anyway. I think it likely that, had he lived, he would have said about the New Left what he wrote in 1960 about the Cuban revolution: "I do not worry about it, I worry for it and with it." (32)

For all that his life was cut short, more of Mills' work endures than that of any other critic of his time. His was an indispensable, brilliant voice in sociology and social criticism—and in the difficult, necessary effort to link the two. He was a restless, engaged, engaging moralist, asking the big questions, keeping open the sense of what an intellectual's life might be. His work is bracing, often thrilling, even when one disagrees. One reads and rereads with a feeling of being challenged beyond one's received wisdom, called to one's best thinking, one's highest order of judgment. For an intellectual of our time, no higher praise is possible.

Notes

1) I am deliberately using a word from the little-noted subtitle of Daniel Bell's The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties (New York: Free Press, 1960).

2) This was A. A. Berle, Jr., also a major exponent of the view that management in the modern corporation had taken control from stock owners. Berle, the influential co-author of The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932), had been criticized by Mills for his views of corporate conscience (Mills, The Power Elite [New York: Oxford University Press, 1956], pp. 125n, 126n.). For those who knew this history, the forthcoming debate looked even more like a showdown.

3) From an essay written in the fall of 1957 to "Tovarich," whom Mills imagined as a symbolic Russian opposite number. C. Wright Mills: Letters and Autobiographical Writings, edited by Kathryn Mills with Pamela Mills, ms. p. 276. My thanks to Naomi Schneider of the University of California Press, and Kathryn Mills, for permission to read and quote from the manuscript of that forthcoming book.

4) From a letter-essay addressed to "Tovarich," fall 1957, C. Wright Mills, ms., p. 26.

5) Mills to "Tovarich," C. Wright Mills, ms. p. 30.

6) Mills to "Tovarich," C. Wright Mills, ms. p. 278.

7) Mills to "Tovarich," C. Wright Mills , ms. p. 279.

8) Mills note in his "Tovarich" notebook, June 1960, C. Wright Mills , ms., p. 340.

9) Mills, The Causes of World War Three (New York: Ballantine, 1958, 1960), pp. 185-6.

10) Letter to The Battalion, April 3, 1935, in ms., p. 36.

11) In the late 1960s, Paul Goodman, another exemplary freelance intellectual who inspired the New Left, wrote a piece for The New York Review of Books on what he called "the sweet style of Hemingway," just as the strong silent style was about to pass into the nether world thanks to Kate Millett and other feminists. Goodman, even more than Mills, practiced an instantly recognizable prose style that found grace in lumbering.

12) Mills to "Tovarich," fall 1957, ms. pp. 273-74.

13) Mills to John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, November 7, 1944, pp. 83-84. To the credit of the foundation, he got the grant. This would make for an interesting subject: The way in which, while sociology was hardening into the molds Mills righteously scorned, it had not altogether hardened¾ which permitted the leaders of the field to honor Mills and take him seriously, at least in his early work, while recoiling from his later.

14) Mills to Harvey and Bette Swados, November 3, 1956, in ms., p. 241.

15) The Sociological Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 1959), p. 225.

16) Sociological Imagination, p. 18n.

17) Sociological Imagination, p. 33.

18) I have elaborated on the implied politics of the Theory Class in "Sociology for Whom? Criticism for Whom?, in Herbert J. Gans, ed., Sociology in America, (Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990), pp. 214-226.

19) Sociological Imagination, p. 131.

20) The Marxists (New York: Dell, 1962), p. 12. Mills' italics.

21) Sociological Imagination, p. 192.

22) See the great chapter "On Reason and Freedom," Sociological Imagination, pp. 165-176.

23) Sociological Imagination, p. 166.

24) The Causes of World War Three (New York: Ballantine, 1958, 1960), p. 21.

25) Irving Howe's harsh critique of The Causes of World War III (Dissent, Spring 1959, pp. 191-6) berated Mills for claiming that the U. S. and the U. S. S. R. were converging into a "fearful symmetry" (Causes, p. 9). Howe charged Mills with coming "uncomfortably close" to defending "a kind of 'moral coexistence'" (pp. 195-6), and the two men broke off their relations after the review appeared. In fury at the complacency of American leadership, Mills did at times veer toward the cavalier. Despite his sympathy for East European dissidents, Mills could indeed be, as Howe charged, slapdash about Soviet imperialism in the satellite countries. But subsequent scholarship makes plain just how great was the American "lead" over the Soviet nuclear establishment in the late 1950s, when Mills was writing; how fraudulent was Kennedy's claim of a "missile gap," and therefore how much greater was the American responsibility to back down from nuclear strategies that could easily have eventuated in an exterminating war.

26) Causes, p. 39.

27) In the chapter called "The Conservative Mood" in The Power Elite, Mills did write (p. 331) that "the conservative mood is strong, almost as strong as the pervasive liberal rhetoric," but he did not anticipate that opposition to civil rights and general anti-statism might fuse into popular movements that could eventually take over the Republican party.

28) Riesman, review of White Collar, American Journal of Sociology 16 (1951), pp. 513-5. Mills' "middle levels of power" was a concept aimed directly at Riesman's "veto groups" in The Lonely Crowd. Despite their analytical differences, however, Riesman was devoutly anti-nationalist, and his active commitment to the peace movement of the early 1960s converged at many points with Mills' suspicion of the power elite.

29) Listen, Yankee (New York: Ballantine, 1960), p. 179.

30) Bell, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (New York: Basic, 1976). For one of many examples of Mills anticipating this important argument, see The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1956), p. 384. Bell wrote a scathing critique of The Power Elite (reprinted as "Is There a Ruling Class in America? The Power Elite Reconsidered," Chapter 3 in The End of Ideology ), properly chastising Mills for scanting the differences between New Deal and Republican administrations, but also charging him—in the middle of the twentieth century!¾ with an overemphasis on power as violence. Mills dismissed "Mr. Bell's debater's points" in a letter to Hans Gerth of December 2, 1958, writing that he would not deign to respond publicly (C. Wright Mills, ms. p. 299). This is too bad, because most of Bell's points could have been straightforwardly and convincingly rebutted.

31) Listen, Yankee, p. 183. Mills' italics. It should be remembered that his misjudgments came early in the revolution. He wrote, for example: "The Cuban revolution, unlike the Russian, has, in my judgment, solved the major problems of agricultural production by its agrarian reform." (Listen, Yankee, p. 185). Such are the perils of pamphleteering.

32) Listen, Yankee, p. l 79. Mills' italics.

* Gitlin is a professor in the departments of culture and communication, journalism, and sociology at New York University. He has published seven books, including The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, Inside Prime Time, and a novel, The Murder of Albert Einstein. Gitlin is a columnist for the New York Observer and has also published his writing in publications such as The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, and Boston Globe. He is on the editorial board of Dissent and a contributing editor of the academic journals Theory and Society and Critical Studies in Mass Communication. Gitlin's most recent book The Twilight of Common Dreams: Why America is Wracked by the Culture Wars is an examination of how the fundamental problems of inequality and racial discrimination are often overlooked by activists of identity politics who would rather fight against perceived symbols of insult. The book was a selection of the Book of the Month and History Book Clubs.

Gitlin holds degrees from Harvard University, the University of Michigan, and the University of California at Berkeley. He was the third president of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1963-64, and in 1964-65, the coordinator of the SDS Peace Research and Education Project, during which time he helped organize the first national demonstration against the Vietnam War. In 1968-69, Gitlin was an editor and writer for the San Francisco Express Times. Gitlin served as a professor of sociology and director of the mass communications program at the University of California at Berkeley for sixteen years, after which he accepted his current post as a professor at New York University.

11.3.00

The Power Elite Now

The American Prospect, May 1999

The Power Elite Now

by ALAN WOLFE

Wright Mills's The Power Elite was published in 1956, a time, as Mills himself put it, when Americans were living through "a material boom, a nationalist celebration, a political vacuum." It is not hard to understand why Americans were as complacent as Mills charged.

Let's say you were a typical 35-year-old voter in 1956. When you were eight years old, the stock market crashed, and the resulting Great Depression began just as you started third or fourth grade. Hence your childhood was consumed with fighting off the poverty of the single greatest economic catastrophe in American history. When you were 20, the Japanese invaded Pearl Harbor, ensuring that your years as a young adult, especially if you were male, would be spent fighting on the ground in Europe or from island to island in Asia. If you were lucky enough to survive that experience, you returned home at the ripe old age of 24, ready to resume some semblance of a normal life—only then to witness the Korean War, McCarthyism, and the beginning of the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Into this milieu exploded The Power Elite. C. Wright Mills was one of the first intellectuals in America to write that the complacency of the Eisenhower years left much to be desired. His indictment was uncompromising. On the one hand, he claimed, vast concentrations of power had coagulated in America, making a mockery of American democracy. On the other, he charged that his fellow intellectuals had sold out to the conservative mood in America, leaving their audience—the American people themselves—in a state of ignorance and apathy bearing shocking resemblance to the totalitarian regimes that America had defeated or was currently fighting.

One of the goals Mills set for himself in The Power Elite was to tell his readers—again, assuming that they were roughly 35 years of age—how much the organization of power in America had changed during their lifetimes. In the 1920s, when this typical reader had been born, there existed what Mills called "local society," towns and small cities throughout America whose political and social life was dominated by resident businessmen. Small-town elites, usually Republican in their outlook, had a strong voice in Congress, for most of the congressmen who represented them were either members of the dominant families themselves or had close financial ties to them.

By the time Mills wrote his book, this world of local elites had become as obsolete as the Model T Ford. Power in America had become nationalized, Mills charged, and as a result had also become interconnected. The Power Elite called attention to three prongs of power in the United States. First, business had shifted its focus from corporations that were primarily regional in their workforces and customer bases to ones that sought products in national markets and developed national interests. What had once been a propertied class, tied to the ownership of real assets, had become a managerial class, rewarded for its ability to organize the vast scope of corporate enterprise into an engine for ever-expanding profits. No longer were the chief executive officers of these companies chosen because they were of the right social background. Connections still mattered, but so did bureaucratic skill. The men who possessed those skills were rewarded well for their efforts. Larded with expense accounts and paid handsomely, they could exercise national influence not only through their companies, but through the roles that they would be called upon to serve in "the national interest."

Similar changes had taken place in the military sector of American society. World War II, Mills argued, and the subsequent start of the Cold War, led to the establishment of "a permanent war economy" in the United States. Mills wrote that the "warlords," his term for the military and its civilian allies, had once been "only uneasy, poor relations within the American elite; now they are first cousins; soon they may become elder brothers." Given an unlimited checking account by politicians anxious to appear tough, buoyed by fantastic technological and scientific achievements, and sinking roots into America's educational institutions, the military, Mills believed, was becoming increasingly autonomous. Of all the prongs of the power elite, this "military ascendancy" possessed the most dangerous implications. "American militarism, in fully developed form, would mean the triumph in all areas of life of the military metaphysic, and hence the subordination to it of all other ways of life."

In addition to the military and corporate elites, Mills analyzed the role of what he called "the political directorate." Local elites had once been strongly represented in Congress, but Congress itself, Mills pointed out, had lost power to the executive branch. And within that branch, Mills could count roughly 50 people who, in his opinion, were "now in charge of the executive decisions made in the name of the United States of America." The very top positions—such as the secretaries of state or defense—were occupied by men with close ties to the leading national corporations in the United States. These people were not attracted to their positions for the money; often, they made less than they would have in the private sector. Rather they understood that running the Central Intelligence Agency or being secretary of the Treasury gave one vast influence over the direction taken by the country. Firmly interlocked with the military and corporate sectors, the political leaders of the United States fashioned an agenda favorable to their class rather than one that might have been good for the nation as a whole.

Although written very much as a product of its time, The Power Elite has had remarkable staying power. The book has remained in print for 43 years in its original form, which means that the 35-year-old who read it when it first came out is now 78 years old. The names have changed since the book's appearance—younger readers will recognize hardly any of the corporate, military, and political leaders mentioned by Mills—but the underlying question of whether America is as democratic in practice as it is in theory continues to matter very much.

Changing Fortunes

The obvious question for any contemporary reader of The Power Elite is whether its conclusions apply to the United States today. Sorting out what is helpful in Mills's book from what has become obsolete seems a task worth undertaking.

Each year, Fortune publishes a list of the 500 leading American companies based on revenues. Roughly 30 of the 50 companies that dominated the economy when Mills wrote his book no longer do, including firms in once seemingly impregnable industries such as steel, rubber, and food. Putting it another way, the 1998 list contains the names of many corporations that would have been quite familiar to Mills: General Motors is ranked first, Ford second, and Exxon third. But the company immediately following these giants—Wal-Mart Stores—did not even exist at the time Mills wrote; indeed, the idea that a chain of retail stores started by a folksy Arkansas merchant would someday outrank Mobil, General Electric, or Chrysler would have startled Mills. Furthermore, just as some industries have declined, whole new industries have appeared in America since 1956; IBM was fifty-ninth when Mills wrote, hardly the computer giant—sixth on the current Fortune 500 list—that it is now. (Compaq and Intel, neither of which existed when Mills wrote his book, are also in the 1998 top 50.) To illustrate how closed the world of the power elite was, Mills called attention to the fact that one man, Winthrop W. Aldrich, the American ambassador to Great Britain, was a director of 4 of the top 25 companies in America in 1950. In 1998, by contrast, only one of those companies, AT&T, was at the very top; of the other three, Chase Manhattan was twenty-seventh, Metropolitan Life had fallen to forty-third, and the New York Central Railroad was not to be found.

Despite these changes in the nature of corporate America, however, much of what Mills had to say about the corporate elite still applies. It is certainly still the case, for example, that those who run companies are very rich; the gap between what a CEO makes and what a worker makes is extraordinarily high. But there is one difference between the world described by Mills and the world of today that is so striking it cannot be passed over. As odd as it may sound, Mills's understanding of capitalism was not radical enough. Heavily influenced by the sociology of its time, The Power Elite portrayed corporate executives as organization men who "must 'fit in' with those already at the top." They had to be concerned with managing their impressions, as if the appearance of good results were more important than the actuality of them. Mills was disdainful of the idea that leading businessmen were especially competent. "The fit survive," he wrote, "and fitness means, not formal competence—there probably is no such thing for top executive positions—but conformity with the criteria of those who have already succeeded."

It may well have been true in the 1950s that corporate leaders were not especially inventive; but if so, that was because they faced relatively few challenges. If you were the head of General Motors in 1956, you knew that American automobile companies dominated your market; the last thing on your mind was the fact that someday cars called Toyotas or Hondas would be your biggest threat. You did not like the union which organized your workers, but if you were smart, you realized that an ever-growing economy would enable you to trade off high wages for your workers in return for labor market stability. Smaller companies that supplied you with parts were dependent on you for orders. Each year you wanted to outsell Ford and Chrysler, and yet you worked with them to create an elaborate set of signals so that they would not undercut your prices and you would not undercut theirs. Whatever your market share in 1956, in other words, you could be fairly sure that it would be the same in 1957. Why rock the boat? It made perfect sense for budding executives to do what Mills argued they did do: assume that the best way to get ahead was to get along and go along.

Very little of this picture remains accurate at the end of the twentieth century. Union membership as a percentage of the total workforce has declined dramatically, and while this means that companies can pay their workers less, it also means that they cannot expect to invest much in the training of their workers on the assumption that those workers will remain with the company for most of their lives. Foreign competition, once negligible, is now the rule of thumb for most American companies, leading many of them to move parts of their companies overseas and to create their own global marketing arrangements. America's fastest-growing industries can be found in the field of high technology, something Mills did not anticipate. ("Many modern theories of industrial development," he wrote, "stress technological developments, but the number of inventors among the very rich is so small as to be unappreciable.") Often dominated by self-made men (another phenomenon about which Mills was doubtful), these firms are ruthlessly competitive, which upsets any possibility of forming gentlemen's agreements to control prices; indeed, among internet companies the idea is to provide the product with no price whatsoever—that is, for free—in the hopes of winning future customer loyalty.

These radical changes in the competitive dynamics of American capitalism have important implications for any effort to characterize the power elite of today. C. Wright Mills was a translator and interpreter of the German sociologist Max Weber, and he borrowed from Weber the idea that a heavily bureaucratized society would also be a stable and conservative society. Only in a society which changes relatively little is it possible for an elite to have power in the first place, for if events change radically, then it tends to be the events controlling the people rather than the people controlling the events. There can be little doubt that those who hold the highest positions in America's corporate hierarchy remain, as they did in Mills's day, the most powerful Americans. But not even they can control rapid technological transformations, intense global competition, and ever-changing consumer tastes. American capitalism is simply too dynamic to be controlled for very long by anyone.

The Warlords

One of the crucial arguments Mills made in The Power Elite was that the emergence of the Cold War completely transformed the American public's historic opposition to a permanent military establishment in the United States. Indeed, he stressed that America's military elite was now linked to its economic and political elite. Personnel were constantly shifting back and forth from the corporate world to the military world. Big companies like General Motors had become dependent on military contracts. Scientific and technological innovations sponsored by the military helped fuel the growth of the economy. And while all these links between the economy and the military were being forged, the military had become an active political force. Members of Congress, once hostile to the military, now treated officers with great deference. And no president could hope to staff the Department of State, find intelligence officers, and appoint ambassadors without consulting with the military.

Mills believed that the emergence of the military as a key force in American life constituted a substantial attack on the isolationism which had once characterized public opinion. He argued that "the warlords, along with fellow travelers and spokesmen, are attempting to plant their metaphysics firmly among the population at large." Their goal was nothing less than a redefinition of reality—one in which the American people would come to accept what Mills called "an emergency without a foreseeable end." "War or a high state of war preparedness is felt to be the normal and seemingly permanent condition of the United States," Mills wrote. In this state of constant war fever, America could no longer be considered a genuine democracy, for democracy thrives on dissent and disagreement, precisely what the military definition of reality forbids. If the changes described by Mills were indeed permanent, then The Power Elite could be read as the description of a deeply radical, and depressing, transformation of the nature of the United States.

Much as Mills wrote, it remains true today that Congress is extremely friendly to the military, at least in part because the military has become so powerful in the districts of most congressmen. Military bases are an important source of jobs for many Americans, and government spending on the military is crucial to companies, such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing, which manufacture military equipment. American firms are the leaders in the world's global arms market, manufacturing and exporting weapons everywhere. Some weapons systems never seem to die, even if, as was the case with a "Star Wars" system designed to destroy incoming missiles, there is no demonstrable military need for them.

Yet despite these similarities with the 1950s, both the world and the role that America plays in that world have changed. For one thing, the United States has been unable to muster its forces for any sustained use in any foreign conflict since Vietnam. Worried about the possibility of a public backlash against the loss of American lives, American presidents either refrain from pursuing military adventures abroad or confine them to rapid strikes, along the lines pursued by Presidents Bush and Clinton in Iraq. Since 1989, moreover, the collapse of communism in Russia and Eastern Europe has undermined the capacity of America's elites to mobilize support for military expenditures. China, which at the time Mills wrote was considered a serious threat, is now viewed by American businessmen as a source of great potential investment. Domestic political support for a large and permanent military establishment in the United States, in short, can no longer be taken for granted.

The immediate consequence of these changes in the world's balance of power has been a dramatic decrease in that proportion of the American economy devoted to defense. At the time Mills wrote, defense expenditures constituted roughly 60 percent of all federal outlays and consumed nearly 10 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product. By the late 1990s, those proportions had fallen to 17 percent of federal outlays and 3.5 percent of GDP. Nearly three million Americans served in the armed forces when The Power Elite appeared, but that number had dropped by half at century's end. By almost any account, Mills's prediction that both the economy and the political system of the United States would come to be ever more dominated by the military is not borne out by historical developments since his time.

And how could he have been right? Business firms, still the most powerful force in American life, are increasingly global in nature, more interested in protecting their profits wherever they are made than in the defense of the country in which perhaps only a minority of their employees live and work. Give most of the leaders of America's largest companies a choice between invading another country and investing in its industries and they will nearly always choose the latter over the former. Mills believed that in the 1950s, for the first time in American history, the military elite had formed a strong alliance with the economic elite. Now it would be more correct to say that America's economic elite finds more in common with economic elites in other countries than it does with the military elite of its own. The Power Elite failed to foresee a situation in which at least one of the key elements of the power elite would no longer identify its fate with the fate of the country which spawned it.

Mass Society and the Power Elite

Politicians and public officials who wield control over the executive and legislative branches of government constitute the third leg of the power elite. Mills believed that the politicians of his time were no longer required to serve a local apprenticeship before moving up the ladder to national politics. Because corporations and the military had become so interlocked with government, and because these were both national institutions, what might be called "the nationalization of politics" was bound to follow. The new breed of political figure likely to climb to the highest political positions in the land would be those who were cozy with generals and CEOs, not those who were on a first-name basis with real estate brokers and savings and loan officials.

For Mills, politics was primarily a facade. Historically speaking, American politics had been organized on the theory of balance: each branch of government would balance the other; competitive parties would ensure adequate representation; and interest groups like labor unions would serve as a counterweight to other interests like business. But the emergence of the power elite had transformed the theory of balance into a romantic, Jeffersonian myth. So anti democratic had America become under the rule of the power elite, according to Mills, that most decisions were made behind the scenes. As a result, neither Congress nor the political parties had much substantive work to carry out. "In the absence of policy differences of consequence between the major parties," Mills wrote, "the professional party politician must invent themes about which to talk."

Mills was right to emphasize the irrelevance of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century images to the actualities of twentieth-century American political power. But he was not necessarily correct that politics would therefore become something of an empty theatrical show. Mills believed that in the absence of real substance, the parties would become more like each other. Yet today the ideological differences between Republicans and Democrats are severe—as, in fact, they were in 1956. Joseph McCarthy, the conservative anticommunist senator from Wisconsin who gave his name to the period in which Mills wrote his book, appears a few times in The Power Elite, but not as a major figure. In his emphasis on politics and economics, Mills underestimated the important role that powerful symbolic and moral crusades have had in American life, including McCarthy's witch-hunt after communist influence. Had he paid more attention to McCarthyism, Mills would have been more likely to predict the role played by divisive issues such as abortion, immigration, and affirmative action in American politics today. Real substance may not be high on the American political agenda, but that does not mean that politics is unimportant. Through our political system, we make decisions about what kind of people we imagine ourselves to be, which is why it matters a great deal at the end of the twentieth century which political party is in power.

Contemporary commentators believe that Mills was an outstanding social critic but not necessarily a first-rate social scientist. Yet I believe that The Power Elite survives better as a work of social science than of social criticism.

At the time Mills was writing, academic sociology was in the process of proclaiming itself a science. The proper role of the sociologist, many of Mills's colleagues believed, was to conduct value-free research emphasizing the close empirical testing of small-bore hypotheses. A grand science would eventually be built upon extensive empirical work which, like the best of the natural sciences, would be published in highly specialized journals emphasizing methodological innovation and technical proficiency. Because he never agreed with these objectives, Mills was never considered a good scientist by his sociological peers.

Yet not much of the academic sociology of the 1950s has survived, while The Power Elite, in terms of longevity, is rivaled by very few books of its period. In his own way, Mills contributed much to the understanding of his era. Social scientists of the 1950s emphasized pluralism, a concept which Mills attacked in his criticisms of the theory of balance. The dominant idea of the day was that the concentration of power in America ought not be considered excessive because one group always balanced the power of others. The biggest problem facing America was not concentrated power but what sociologists began to call "the end of ideology." America, they believed, had reached a point in which grand passions over ideas were exhausted. From now on, we would require technical expertise to solve our problems, not the musings of intellectuals.

Compared to such ideas, Mills's picture of American reality, for all its exaggerations, seems closer to the mark. If the test of science is to get reality right, the very passionate convictions of C. Wright Mills drove him to develop a better empirical grasp on American society than his more objective and clinical contemporaries. We can, therefore, read The Power Elite as a fairly good account of what was taking place in America at the time it was written.

As a social critic, however, Mills leaves something to be desired. In that role, Mills portrays himself as a lonely battler for the truth, insistent upon his correctness no matter how many others are seduced by the siren calls of power or wealth. This gives his book emotional power, but it comes with a certain irresponsibility. "In Am erica today," Mills wrote in a typical passage, "men of affairs are not so much dogmatic as they are mindless." Yet however one may dislike the decisions made by those in power in the 1950s, as decisionmakers they were responsible for the consequences of their acts. It is often easier to criticize from afar than it is to get a sense of what it actually means to make a corporate decision involving thousands of workers, to consider a possible military action that might cost lives, or to decide whether public funds should be spent on roads or welfare. In calling public officials mindless, Mills implies that he knows how they might have acted better. But if he did, he never told readers of The Power Elite; missing from the book is a statement of what concretely could be done to make the world accord more with the values in which Mills believed.

It is, moreover, one thing to attack the power elite, yet another to extend his criticisms to other intellectuals—and even the public at large. When he does the latter, Mills runs the risk of becoming as antidemocratic as he believed America had become. As he brings his book to an end, Mills adopts a term once strongly identified with conservative political theorists. Appalled by the spread of democracy, conservative European writers proclaimed the twentieth century the age of "mass society." The great majority, this theory held, would never act rationally but would respond more like a crowd, hysterically caught up in frenzy at one point, apathetic and withdrawn at another. "The United States is not altogether a mass society," Mills wrote—and then he went on to write as if it were. And when he did, the image he conveyed of what an American had become was thoroughly unattractive: "He loses his independence, and more importantly, he loses the desire to be independent; in fact, he does not have hold of the idea of being an independent individual with his own mind and his own worked-out way of life." Mills had become so persuaded of the power of the power elite that he seemed to have lost all hope that the American people could find themselves and put a stop to the abuses he detected.

One can only wonder, then, what Mills would have made of the failed attempt by Republican zealots to impeach and remove the President of the United States. At one level it makes one wish there really were a power elite, for surely such an elite would have prevented an extremist faction of an increasingly ideological political party from trying to overturn the results of two elections. And at another level, to the degree that America weathered this crisis, it did so precisely because the public did not act as if were numbed by living in a mass society, for it refused to follow the lead of opinion makers, it made up its mind early and thoughtfully, and then it held tenaciously to its opinion until the end.

Whether or not America has a power elite at the top and a mass society at the bottom, however, it remains in desperate need of the blend of social science and social criticism which The Power Elite offered. It would take another of Mills's books—perhaps The Sociological Imagination—to explain why that has been lost.

Alan Wolfe

Copyright © 1999 by The American Prospect, Inc. Preferred Citation: Alan Wolfe, "The Power Elite Now," The American Prospect vol. 10 no. 44, May 1, 1999 - June 1, 1999. This article may not be resold, reprinted, or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission from the author. Direct questions about permissions to permissions@prospect.org.

10.3.00

H.T. Reynolds: The Power Elite

THE POWER ELITE

Thomas Dye, a political scientist, and his students have been studying the upper echelons of leadership in America since 1972. These "top positions" encompassed the posts with the authority to run programs and activities of major political, economic, legal, educational, cultural, scientific, and civic institutions. The occupants of these offices, Dye's investigators found, control half of the nation's industrial, communications, transportation, and banking assets, and two-thirds of all insurance assets. In addition, they direct about 40 percent of the resources of private foundations and 50 percent of university endowments. Furthermore, less than 250 people hold the most influential posts in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the federal government, while approximately 200 men and women run the three major television networks and most of the national newspaper chains.

Facts like these, which have been duplicated in countless other studies, suggest to many observers that power in the United States is concentrated in the hands of a single power elite. Scores of versions of this idea exist, probably one for each person who holds it, but they all interpret government and politics very differently than pluralists. Instead of seeing hundreds of competing groups hammering out policy, the elite model perceives a pyramid of power. At the top, a tiny elite makes all of the most important decisions for everyone below. A relatively small middle level consists of the types of individuals one normally thinks of when discussing American government: senators, representatives, mayors, governors, judges, lobbyists, and party leaders. The masses occupy the bottom. They are the average men and women in the country who are powerless to hold the top level accountable.

The power elite theory, in short, claims that a single elite, not a multiplicity of competing groups, decides the life-and-death issues for the nation as a whole, leaving relatively minor matters for the middle level and almost nothing for the common person. It thus paints a dark picture. Whereas pluralists are somewhat content with what they believe is a fair, if admittedly imperfect, system, the power elite school decries the grossly unequal and unjust distribution of power it finds everywhere.

People living in a country that prides itself on democracy, that is surrounded by the trappings of free government, and that constantly witnesses the comings and goings of elected officials may find the idea of a power elite farfetched. Yet many very intelligent social scientists accept it and present compelling reasons for believing it to be true. Thus, before dismissing it out of hand, one ought to listen to their arguments.

Characteristics of the Power Elite

According to C. Wright Mills, among the best known power-elite theorists, the governing elite in the United States draws its members from three areas: (1) the highest political leaders including the president and a handful of key cabinet members and close advisers; (2) major corporate owners and directors; and (3) high-ranking military officers.

Even though these individuals constitute a close-knit group, they are not part of a conspiracy that secretly manipulates events in their own selfish interest. For the most part, the elite respects civil liberties, follows established constitutional principles, and operates openly and peacefully. It is not a dictatorship; it does not rely on terror, a secret police, or midnight arrests to get its way. It does not have to, as we will see.

Nor is its membership closed, although many members have enjoyed a head start in life by virtue of their being born into prominent families. Nevertheless, those who work hard, enjoy good luck, and demonstrate a willingness to adopt elite values do find it possible to work into higher circles from below.

If the elite does not derive its power from repression or inheritance, from where does its strength come? Basically it comes from control of the highest positions in the political and business hierarchy and fromv shared values and beliefs.

Top Command Posts.

In the first place, the elite occupies what Mills terms the top command posts of society. These positions give their holders enormous authority over not just governmental, but financial, educational, social, civic, and cultural institutions as well. A small group is able to take fundamental actions that touch everyone. Decisions made in the boardrooms of large corporations and banks affect the rates of inflation and employment. The influence of the chief executive officers of the IBM and DuPont corporations often rivals that of the secretary of commerce. In addition, the needs of industry greatly determine the priorities and policies of educational and research organizations, not to mention the chief economic agencies of government.

The power of the elite has also been enhanced by the close collaboration of political, industrial, and military organizations. As Washington has been called upon to play a more active role in domestic life, from regulating the business cycle to inspecting children's sleepwear, government has come to depend on the corporate world to carry out many of its activities. Conversely, industry now relies heavily on federal supports, subsidies, protection, and loans to ensure the success of its ventures. To be sure, business people and politicians constantly carp at each other. But the fact remains that they have grown so close that they prosper together far more than they do separately.

At the same time, the Cold War has elevated the prestige and power of the military establishment. The United States has come a long way from the days of citizen-soldiers to its present class of professional warriors whose impact far transcends mere military affairs. The demands of foreign affairs, the dangers of potential adversaries, the sophistication and mystique of new weapons, and especially the development of the means of mass destruction have all given power and prestige to our highest military leaders.

As a group, then, this ruling triumvirate of politicians, corporate executives, and military officers has, by virtue of the positions they hold, unprecedented authority to make decisions of national and international consequence. But the mere occupancy of these command posts does not fully explain the effectiveness of their power. Of equal significance is their common outlook on life and their ability and willingness to act harmoniously on basic issues.

Shared Attitudes and Beliefs.

Leafing through the pages of Time or Newsweek one quickly realizes that the members of the so-called power elite constantly squabble among themselves. Such disagreements, which have become part of the background noise of national politics, occur so frequently as to be taken as proof that not one but a multiplicity of elites exist.

According to Mills and others, however, these differences are vastly overshadowed by agreement on a world view. This world view is a set of values, beliefs, and attitudes that shapes the elite's perceptions of government and prevents deep divisions from arising.

Members of the elite agree on the basic outlines of the free enterprise system including profits, private property, the unequal and concentrated distribution of wealth, and the sanctity of private economic power. They take giantism in the world of commerce for granted. More important, they are united in their belief that the primary responsibility of government is to maintain a favorable climate for business. Other governmental responsibilities, such as social welfare and concern for the environment, are secondary to that task.

What produces the acceptance of this world view? Participants in the elite tend to read the same newspapers, join the same clubs, live in the same neighborhoods, send their children to the same schools (usually private and the ones they themselves attended), and belong to the same churches and charities. They work and play together, employ one another, and intermarry. They share, in a word, a life-style that brings them together in mutually reinforcing contact.

Moreover, they undergo similar apprenticeships. Dye finds that 54 percent of the top corporate leaders and 42 percent of our highest political officials went to just 12 private colleges including Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and Stanford.

But it is while advancing through their professions that the unity of thought begins to emerge. By the time men and women reach the top of the corporate or professional ladder, their common experiences have given them a shared way of looking at economics and politics so that they experience and react to events in the same ways. When they enter public service these people cannot, as Mills explains, shed their heritage:

The interesting point is how impossible it is for such [political appointees] to divest themselves of their engagement with the corporate world in general and with their own corporations in particular. Not only their money, but their friends, their interests, their training--their lives in short--are deeply involved in this world...The point is not so much financial or personal interests in a given corporation, but identification with the corporate world. To ask a man suddenly to divest himself of these interests and sensibilities is almost like asking a man to become a woman.

This inability to "divest" oneself of one's past is perhaps what once led a former chairman of General Motors to declare "What's good for GM is good for America."

Candidates: Insiders and Outsiders

Since the early 1970s when politics really began to develop a bad name--a negative reputation over and above the traditional distrust of politicians (see the essay on general-welfare liberalism or the quotes about politicians and parties)--candidates for national office frequently tell voters that they are outsiders, that they are not part of the "establishment," that they will bring fresh faces and new ideas to Washington. Aspirants to office in the 1990s have been especially noteworthy for making this claim. What is interesting to note is that more often than not these candidates and the individuals they work with or appoint to office are themselves insiders, as the recent cabinet appointments suggest.

Distribution of Political Power

Having seen how the governing elite derives its strength, it is important to consider how this power is exercised in the political arena. What roles do the three parts of the pyramid--the elite, the middle level, and the masses--play in American politics?

The Role of the Elite in Making "Trunk Decisions."

Imagine a tree in the dead of winter. With its leaves gone its outline is clearly visible. At the bottom, of course, is the trunk--cut it and the whole tree topples. Higher up three or four main branches support lesser branches, which in turn support still smaller ones until one comes to the twigs at the edges. Cutting the twigs does not change the tree very much. As one saws off branches lower down, however, the shape--and possibly the existence of the tree--is affected. In other words, to determine the direction and extent of growth of the tree, one cannot simply prune off a few boughs at the top but has to cut main limbs or the trunk.

Public policies can be thought of in the same way. There is a hierarchy among them in the sense that some (corresponding to the trunk and main branches) support others. Trunk decisions represent basic choices--whether or not welfare the federal budget must be balanced in seven years, for example--that, once decided, necessitate making lesser choices--cutting food stamps or Aid to Families with Dependent Children. Whoever makes the trunk decisions sets the agenda for subsequent debates about secondary or branch and twig policies.

Let's turn to an issue, the B-1 controversy, raised in the essay on pluralism. As important as it seemed, the B-1 in the eyes of power elite theorists is only a twig. In order to appreciate their contention, ask why the United States needs bombers in the first place. Why not rely on land-based missiles and submarines to deter the Soviet Union?

The answer lies in a prior decision to maintain a "triad," a nuclear retaliatory force consisting of land-based missiles, submarines, and bombers. Having three separate weapons systems, American defense planners concluded, provides an extra margin of safety in the event of a confrontation with the Russians. Are they right? Do we need three types, or could we get along with two? This is an important question--far more important than whether we develop a new bomber or keep an old one--and who decides it structures the debate on this and a host of other issues. Suppose, for a moment, the United States had decided that bombers were unnecessary. The B-1 debate would then be moot and resources allocated to it could be devoted to other purposes such as conventional arms or schools or tax reductions.

Yet the triad is itself only a branch policy; it rests on an even more fundamental policy, containment. Early in the post-World War II era, the United States had to develop a policy toward the Soviet Union. A controversy arose. Some urged a conciliatory approach that would recognize Russia's legitimate security concerns. Others took a harder line. Fearing the spread of international communism, they advocated the use of diplomatic, economic, and especially military means to contain what they perceived to be inexorable Soviet expansionism. The first alternative emphasized cooperation, the second containment; the first implied relatively modest national security efforts, the second enormous expenditures for arms and foreign aid. Ultimately the United States adopted the strategy of containment, which has been the backbone of American foreign policy since 1947.

Containment represents a trunk decision, while most other defense policies such as the triad or the B-1 are either branches or twigs. Containing the Russians put us on a long and arduous path over which we trod for nearly half a century. National defense swallowed a huge portion of the federal budget; it called for the maintenance of an enormous peacetime army; it led us into alliances with nations in the farthest corners of the globe, including some of the most corrupt and dictatorial regimes on earth; it demanded massive military aid programs; it consumed the talents of our scientific establishment and the attention of our national leaders. In short, containment, unlike the B-1, was no ordinary policy but a fundamental commitment of American resources and energies.

Who decides trunk decisions like these? According to the power elite theory, the top of the pyramid usually does. Or it has greatest influence on their formation. The middle levels of government (the Congress, the courts, the states) worry mainly about how best to implement them. This seems to have been the case in the period after World War II when containment first emerged. Most of the key decisions were made behind closed doors in the White House, the State Department, and the Pentagon. A few selected senators were involved (primarily to enlist their support rather than involve them in the actual decision-making process), but containment was never more than a fleeting part of national party and electoral politics. Instead, once the policy had been formulated at the top it was sold to the public.

The Middle Level of Politics.

Where does this put the workaday politicians, the inhabitants of the middle level of politics? Sadly, the elite school reports, their influence has largely dissipated over the years, leaving them with only the outer limbs and twigs to manage. It is certainly true that government in the middle is colorful and noisy and attracts the attention of the popular press. But for the most part its activities hide an important point: Far from competing with the power elite, professional politicians today have lost their ability to control the nation's destiny.